6 tips for editing your own work — and why you should solicit feedback from others

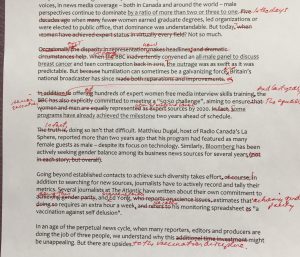

by Shari Graydon Be honest: if you sent me a piece of your writing, and I sent it back marked up like the page at the right, would you feel insulted?

Be honest: if you sent me a piece of your writing, and I sent it back marked up like the page at the right, would you feel insulted?

I know it’s sobering to see words you’ve carefully committed to paper marked up in red ink by a critic who deems your prose something short of deathless. (To soften the blow, when I edit others’ work, I set my track changes preferences so the suggestions show up in teal.) But what’s the point of sharing your hard-won insights, insightful research or compelling stories if they’re written in a way that fails to engage or, worse, causes confusion or frustration?

The good news is, you get used to it – especially if you’re open-minded enough to recognize when someone else’s fresh eyes or sharp pencil has improved your writing.

But before you subject your draft to someone else’s critique, it’s enormously useful to be able to take a red pen to your own words. That’s what you’re looking at: the marked up copy is mine, as are the edits. I try to be as ruthless with my own writing as I am with others. Even before I send it to a colleague or my partner, knowing that they’re likely to spot things I might miss, I attack my own prose as if it were someone else’s.

Here are six strategies to adapt to your own writing:

- Put the draft aside for 24 hours (or even one, if you’re on deadline), so you can read your sentences with slightly refreshed eyes.

- Print it out — because you see material differently on the page than you do on the screen.

- Read it aloud. You will notice when a sentence is too long, or lacking in clarity. If you stumble half-way through, that’s often a signal that you could make it easier on the reader, even if she’s likely to be reading in her head, not aloud.

- Underline key words and phrases that you’ve repeated. Then revise the sentences to reduce the repetition by replacing them with pronouns or synonyms, and making better use of transitions.

- Make sure every sentence adds value. Does the information provided further the argument, offer necessary specifics, help make your conclusion or request inexorable?

- Tighten the sentences. Overwriting is very common, and most people’s first drafts boast longer-than-necessary explanations and redundant words or phrases.

Here’s a quick sample of tightening I performed on my own sentences (all from the same op ed!)

Ed Yong, who reports on science issues

… science reporter Ed Yong;

refers to his monitoring spreadsheet as…

… calls his monitoring spreadsheet;

Five decades ago when many fewer women earned graduate degrees…

… In the days when few women earned graduate degrees;

as a means of celebrating news organizations that are leading by example, and motivating those lagging behind

… to celebrate news organizations that lead by example and motivate those that lag behind

We add news sources each week in pursuit of our goal to

… We add new sources each week to

For a few years in the mid 2000s, I wrote speeches for a couple of federal health ministers and the Governor General. The sign taped above my computer reminded me, “If it’s not necessary to say, it’s necessary not to say.” I’ve found this advice to be relevant to virtually every piece of writing I’ve done since — from emails to op eds to funding proposals. Nobody wants to spend more time reading your content than is justified by its value.

If you’ve taken one of our Writing Compelling Commentary workshops, you would have received an invitation to send me your draft op ed for feedback. Hundreds have taken me up on this offer, receiving one-on-one editing suggestions in advance of submitting to the publication they aspired to appear in.

Although a few have been discouraged or insulted by my recommended revisions, most have appreciated a second set of eyes more familiar with grammar rules, practiced at eliminating wordiness and distanced enough from the material to be able to flag the bits that might be unclear. And many of those draft commentaries ended up published in well-read news platforms reaching audiences of hundreds of thousands of people.

That kind of reach and the potential impact it can achieve — eradicating ignorance, shifting attitudes and changing policies — is worth the short-term discomfort of having someone flag a few unclear sentences, misplaced commas or unsupported claims.

I have learned so much from the editing feedback of others. In the late 1990s, Dawn Rae Downton, a former MediaWatch board colleague, hired me to write a viewer’s guide to accompany a sex education video resource for parents. By that time, I’d been so frequently published, with minimal editing intervention, that when I received my submitted draft red-inked like the sample appearing at the top of this page, I briefly reconsidered our friendship.

But her edits made my draft immeasurably better, and significantly improved my own ability to revise my own work and offer valuable feedback to others. And her literary non-fiction is masterfully written. (Just check out the reviews at the link above.)

Stephen King‘s subject matter is worlds away from Dawn Rae’s, and I’m not a fan of horror. But you can’t argue with his blockbuster success: his books have sold more than 350 million copies and three dozen of them have been made into movies. In his On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft, King relates this story about some early editing feedback he received:

Stephen King‘s subject matter is worlds away from Dawn Rae’s, and I’m not a fan of horror. But you can’t argue with his blockbuster success: his books have sold more than 350 million copies and three dozen of them have been made into movies. In his On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft, King relates this story about some early editing feedback he received:

“I got a scribbled comment that changed the way I rewrote my fiction once and forever. Jotted below the machine-generated signature of the editor was this mot:

‘Not bad, but PUFFY. You need to revise for length. Formula: 2nd Draft = 1st Draft – 10%. Good luck.’”

King has a few things going for him as a writer beyond his ability to apply the -10% formula, but it’s pretty good advice for anyone who’s looking to engage an audience. And I found his book on writing so compelling when I read it 20 years ago that I went out and bought one of his novels, despite my distaste for his genre. I bailed the minute the latter got creepy, but the former still sits on my shelf, ready to yield up its insights anew when I need them.

Shari Graydon is the Catalyst of Informed Opinions, a non-profit working to amplify women’s voices and ensure they have as much influence in Canada’s public conversations as men’s.

We train women to speak up more often and share their insights more effectively.

We make them easier for journalists to find.

And your donation can help ensure that women’s perspectives exert influence in every arena that matters.