4 tips for moving past mere ranting to effective persuasion

by Shari Graydon

Photo by Andrea Piacquadio from Pexels

Twitter and Facebook have a lot to answer for: rampant misinformation, spiralling conspiracy theories, plummeting productivity. (And that’s just in my family!)

But I fear social media echo chambers are also undermining our persuasive capacity. It’s so easy to share the stuff we agree with, and condemn the stuff that’s so obviously WRONG, without going to the trouble of making clear why in a way that might shift perspectives. And I think the social media default is spilling over into other media.

I recently read a vivid and engaging blog post about an important issue. I admired the author’s passion and agreed with her sentiments. But I think the piece would have benefited from an extra set of eyes before publication.

In response to what feels like an increasingly polarized world, I have become more attached to finding words likely to bridge the gaps and shift people’s perspectives… to make them question their actions and beliefs, rather than re-affirm their self-righteousness, or dismiss my words out of hand. And as research I referenced in an op ed for University Affairs makes clear, thoughtful commentary can effectively change minds.

But not all writing – even if it’s fuelled by passion and good intentions – is equally effective at doing that.

Here are four key factors that influence whether your words will be rejected as a rant, or considered as an enlightened argument capable of helping others see things differently.

- You only have one chance to make a first impression

“What we present first changes the way people experience what we present next.”

This is the premise of Roberto Cialdini’s best-selling and research-supported book, Pre-suasion – A Revolutionary Way to Influence and Persuade. As he convincingly documents, writing that seeks to persuade goes out of its way not to alienate those who disagree with its premise in the first sentence.

The blog post that helped to inspire this one was full of concrete and compelling evidence supporting the argument being made. But I doubt that very many people in need of persuading would have gotten as far as that evidence. Because the opening sentence summarily and dismissively condemned a person who is beloved by millions of people all over the world. Even if they did keep reading, many would have done so in a defensive “how dare you” mode.

This was so unfortunate. Because towards the end of the piece, the writer related a story that was as affecting as it was relevant, and that gave personal context to the overwhelming amount of data also shared. If the author had opened with this story, and then moved readers more gradually from one piece of evidence to the next, she might have had a chance of making inexorable the condemning conclusion.

- Your chain is only as strong as its weakest link

In fact, the first paragraph of the blog post was personal – but not in a way that strengthened the argument. The author began by expressing her weariness with the pronouncements of the leader in question. Understandable, perhaps, but not very convincing, relative to all the other reasons provided later on.

Because here’s how this works: in fight or flight mode, most of us instinctively go for the jugular. We hone in on our opponent’s area of greatest weakness. In arguments, that means we disregard the legitimate and supported claims and focus instead on the questionable ones. The fact that the writer was tired of the leader was her least defensible point, but it would have given anybody resistant to her argument a reason to dismiss it.

If you have five pieces of evidence to bolster the case you’re making, it’s worth critically assessing each one to determine which, if any, is the weakest. Indeed, in commentary writing workshops, we counsel aspiring op ed writers to anticipate the most likely source of resistance, acknowledge the expected criticism, and then demonstrate why it’s not relevant.

- Punctuation and grammar matter

Observing grammar and punctuation rules doesn’t, on its own, make your writing intelligent or original. But failing to do so renders your arguments harder for readers to understand, and easier to disregard.

Most people who haven’t studied English, journalism or communications after high school probably can’t articulate the formal rules that govern the language. However, many attentive readers can recognize and correct problems when they see them – especially if the problems show up in someone else’s prose. But that’s what editors are for. We all benefit from a second set of eyes, as the acknowledgement section of almost every book you’ve ever read makes clear.

Attaching a singular subject to a plural verb, switching from present tense to past, and then back again within a single paragraph – these are relatively small faults in the grand scheme of things. But they make the reader’s job more difficult, and in an age of declining attention spans, that’s not helpful – particularly if you’re seeking to persuade.

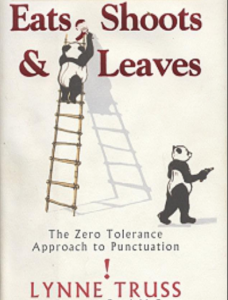

Faulty punctuation – as Lynne Truss, the celebrated author of Eats, Shoots and Leaves made abundantly clear – can dramatically alter the meaning of a sentence. (“Eats shoots and leaves”, without the comma, conjures up an entirely different and less sinister scenario in which visions of a discharged firearm and criminal get-away are replaced with the image of a contented herbivore munching on vegetation.)

Faulty punctuation – as Lynne Truss, the celebrated author of Eats, Shoots and Leaves made abundantly clear – can dramatically alter the meaning of a sentence. (“Eats shoots and leaves”, without the comma, conjures up an entirely different and less sinister scenario in which visions of a discharged firearm and criminal get-away are replaced with the image of a contented herbivore munching on vegetation.)

Teaching business students basic writing skills at Kwantlen University College many years ago, I used to offer the following example: The sentence “Men who are violent hurt women” acknowledges that some men are violent, and they may hurt women. Add a couple of commas, however, and you’re suddenly making the indefensible claim that all men are violent: “Men, who are violent, hurt women.”

4. There’s no excuse for spelling errors

Finally, given that virtually all word processing software comes with a built-in spellcheck, there’s no excuse for spelling errors. These, too, may seem inconsequential, but failing to take the extra few minutes to check the spelling of a word can plant niggling doubts in readers’ minds. Consciously or unconsciously we find ourselves wondering: “If the writer can’t even check her spelling, what else has she gotten wrong? Is the data accurate? Can I rely on the facts supplied, and the conclusions drawn?”

So if your mastery is of formulae, not sentences, if your strength lies in innovative ideas, not detail-oriented execution, it’s smart to enlist input from a wordsmith able to offer the kind of technical support that will complement what you do well by compensating for what you don’t. And it’s also useful to run your argument by someone who either vehemently disagrees with you, or is capable of anticipating the objections of those who do.

Whether you’re writing to convince people of the importance of your ideas, the viability of your project, or the relevance of your recommendations, you don’t want to give them any ammunition to question what you’ve written.

We rely on our ability to persuade others every day, but most of us never learn the basics.

Next month Informed Opinions is offering a new workshop to help rectify that. Register now.

Shari Graydon is the Catalyst of Informed Opinions, a non-profit working to amplify women’s voices and ensure they have as much influence in Canada’s public conversations as men’s.

We train smart women to speak up more often and more effectively.

We make them easier for journalists to find.

And your donation can help ensure that women’s perspectives are heard and exert influence in every arena that matters.