How to reduce your dependency on speaking notes

by Shari Graydon

It’s not always easy to generate this kind of attentive engagement when you’re reading a script.

A woman once told me about having attended her thesis supervisor’s presentation at an academic conference. It took him almost 20 minutes to read his research paper aloud. When he looked up at the end, she was the only one remaining.

Everyone else had bailed from sheer boredom — and he hadn’t even noticed. (She would have too, except… supervisor.)

You don’t want that kind of humiliation. Luckily (unless you’re an audience member), it’s usually not so easy for people to escape. But online presentations both increase the temptation to tune out, and provide a multitude of incentivizing distractions.

Most of us, given the opportunity to craft, revise and polish an argument in writing, can make a more cohesive and compelling case than if we’re speaking off the cuff extemporaneously.

The problem is that the sentences we commit to a page are designed for the eye to read, not for the ear to hear. And I suspect that the attachment people have to their script increases with every year spent in an academic environment, given the anticipated judgment expected from learned colleagues. But as I explained in my most recent post, that affinity is a barrier to engaging your audience.

In 2021, we’ll be offering a new workshop called “Ditching Your Script.” Its aim is to give speakers who are really attached to their notes a risk-free opportunity to learn and apply some tested strategies in front of a very small and supportive audience of peers.

In the meantime, here are a few of the approaches I’ve used to help lessen my own dependency on written notes as a speaker. They all require you to refrain from writing your notes in full, linear sentences.

You speak every day to colleagues and clients, friends and family members without the aid of a script. You successfully communicate your ideas, convey your enthusiasm, achieve your goals. You don’t need the script.

And if you never draft it in the first place, you won’t become attached to using it. Instead, the next time you’re preparing for a presentation, try one of the following:

- Make an outline in bullet points. Keep it to one page if you can. Structure helps.

Depending on the topic, your organizing framework could be as simple as “Problem/Solution”, “Policy/Consequence/Alternative”, or “5 things we need to consider when…”

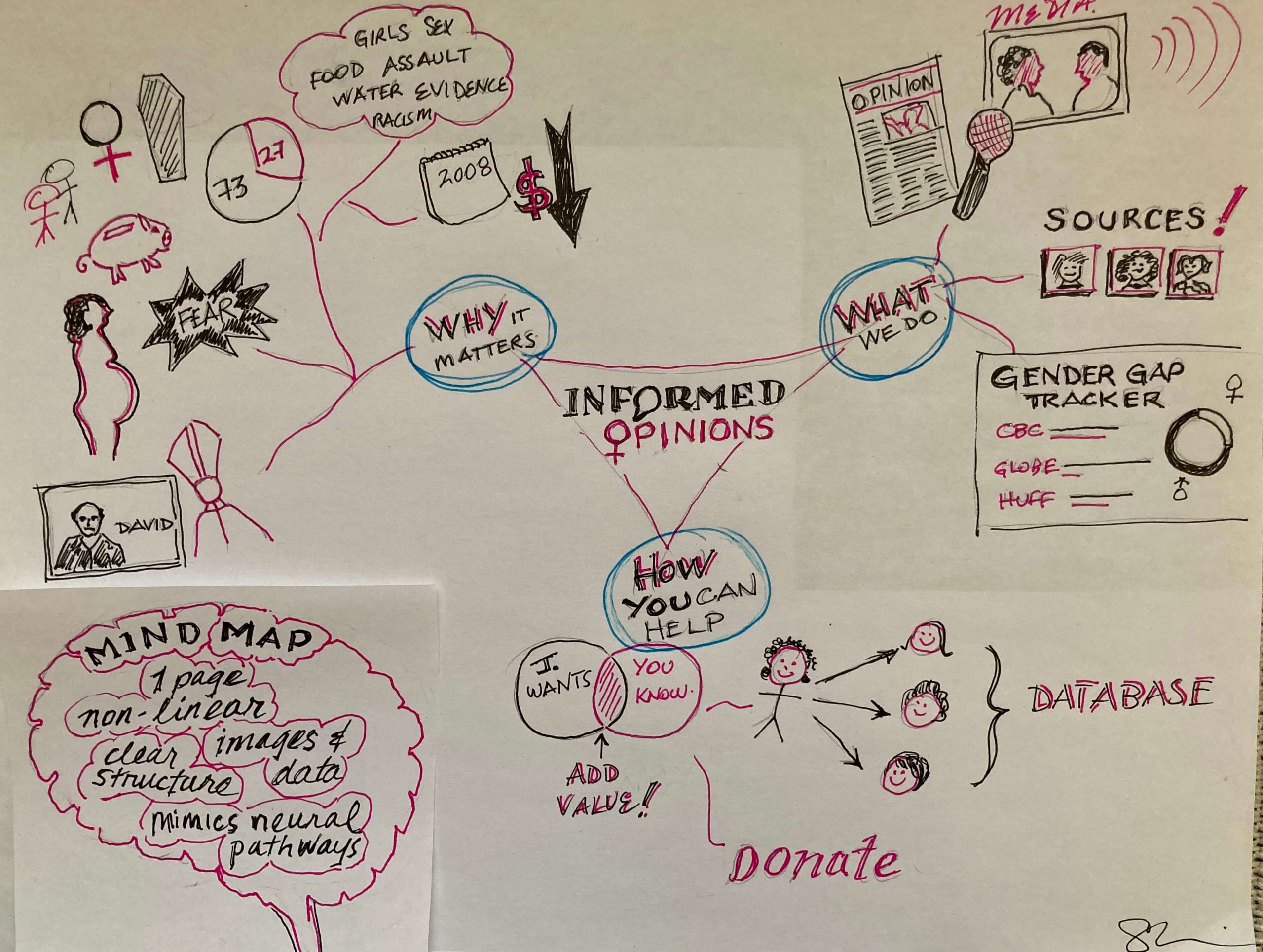

For example, when I’m speaking about Informed Opinions in an informal situation without the benefit of a slide deck (see strategy 3), I often employ a 3-point outline consisting of “why this matters, what we’re doing about it, and how you can become involved.”

Being explicit about your framework up front gives you a road map so you don’t veer widely off-track. And sharing it has the added value of increasing your audience’s attentiveness: you are essentially priming them to listen for the markers that signal the progression of your talk. You’ve made it easier for them to both follow and remember your message.

- Draw a mind map. This is a particularly useful tool for both panel presentations and media interviews.

On a single page, using as few words as possible, you organize the information you want to cover by categories or questions (much like your outline structure described above). But rather than doing so in a linear list, you’re creating a more organic chart. And you’re deliberately replacing full sentences or long phrases with individual words, relevant statistics, names and rudimentary pictures.

These are designed to trigger your recall of the more complex associations, examples or details without forcing you to read the fully articulated sentence. As a result, you end up delivering the information in a more conversational way.

For a speech, you can order the limbs of your mind map so you know which order to follow. For a panel discussion or media interview, you can cross off sections as you share the information they contain — or when another panelist has already effectively made the point.

- Populate a deck with images and/or minimal-text take-aways, and use the slides as cues for your content.

This is a common approach, and not, in and of itself, effective. It can be either very engaging or absolutely deadly. The difference is generally:

- The quality of your slide deck,

- Whether you’ve embraced the wisdom about what visual aids are supposed to do (be visual, and aid — the audience, not you) and

- The quality of your verbal delivery.

But if you’re hoping the slides will distract people from the fact that you’re reading your notes in presenter mode, see previous blog post.

If the slides themselves contain long sentences, quotes or bullets, or a lot of text of any kind, then you’re likely either reading the text off your slides verbatim (and that’s annoying because we can read it faster), or you’re competing with yourself, making us choose between listening to you, reading your slides, or giving up in confusion. Because we can’t read a written message and simultaneously absorb the verbally delivered one.

Slides cluttered with multiple small images or exhaustively detailed graphs that include a raft of irrelevant-to-the-point specifics have a hard time fulfilling the obligation implied by “aid”.

But if you have strong, relevant and evocative or explanatory visuals that genuinely cue the content you then deliver in a lively, engaging and natural way, that’s great.

- Build your talk around stories. Identify relatable stories or concrete examples to set up each of the key ideas you intend to explore. Share the example or story and use it as a bridge to the other relevant details, ideas or key takeaways.

Stories are easier to remember than theoretical frameworks or data sets. And they don’t have to be long. In fact, although you want to include enough detail to make the people, circumstances, conflict and resolution vivid, you also want to be concise enough that your audience doesn’t start wondering what your point is.

I often use this approach if forced to condense content I ordinarily deliver in 40 minutes into 10. Good stories deliver on an emotional level and are literally more engaging: they generate more neurological activity in listeners’ brains. As a result, they’re also more memorable than data, and help audiences retain the take-aways you’re aiming to deliver.

If this strategy appeals, but you’re not practiced in the art of identifying and telling stories in a professional context, we have an upcoming workshop about that, too: Applied Storytelling to Engage Audiences (sign up here to receive notifications of upcoming workshops).

- Craft your own hybrid using two or more of the above suggestions.

I have used all of these strategies, often in combination. What matters is not how but whether you ditch the speaking notes. Everybody’s different, and an approach that liberates one person may not help others. So find what works for you.

Whichever method you adopt, I promise you some, if not all, of the following:

- More engaged audiences;

- Invaluable feedback about what to keep, what to ditch and what to clarify or improve the next time you present the similar material;

- A stronger sense of connection with the people you’re speaking to;

- An enhanced capacity to relax in front of a room and show up as yourself;

- More generous questions and comments from the audience;

- Greater confidence in your ability to communicate, to improvise and to engage.

We’re offering a new iteration of our online Master Class in Presentation Skills starting in late January if you’re interested in the opportunity to hone your skills in an 8-week small-group, supportive environment. Find out more here.

Shari Graydon is the Catalyst of Informed Opinions, a non-profit working to amplify women’s voices and ensure they have as much influence in Canada’s public conversations as men’s.

We train women to speak up more often and share their insights more effectively.

We make them easier for journalists to find.

And your donation can help ensure that women’s perspectives exert influence in every arena that matters.