Clear speech advocate writes; Twitter sh*t storm erupts.

by Shari Graydon

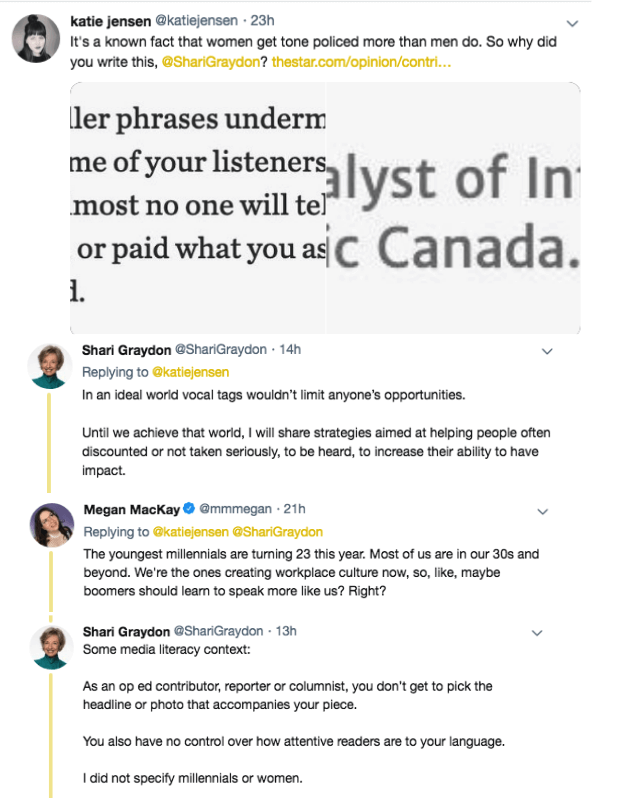

These are just a few of the exchanges provoked by the Toronto Star’s recent publication of a commentary I wrote about the downside of filler phrases.

Many of those who responded on Twitter took issue with my apparent ageism. (Although I referenced recent interaction with young people, I also mentioned that the habit isn’t confined to youth. But the headline used the word “millennials”, which appears to have hit a nerve, and many clearly feel defensive as a result. I regret that.)

The article was also originally accompanied by a photo of two young women, which primed readers to interpret my analysis as being directed at women — which, again, it was not. (The very responsive Scott Colby has since changed this.) But the impact of the photo and headline underlines one of the points we make in many of our workshops:

What you say first, influences the way people will hear and interpret what you say next.

(Indeed, noted persuasion expert Robert Cialdini’s most recent book, Pre-Suasion, a fascinating read, is devoted to exploring exactly that.)

Here’s my piece with the original headline. Additional context follows at the end.

‘I want to like, hire you, but like … really?’

The disease is highly contagious and there’s no vaccine. That’s the bad news. The good news is there is a cure. It requires no doctors or pharmacists, but a bit of mindfulness (perhaps supplemented by a small monetary incentive) and the enrolment of close colleagues and family members.

I’m talking about the vocal tag epidemic in which the interjection of “like” — or “I mean” or “you know” — has become as ubiquitous in some young people’s speech as birdsong in a Canadian spring (but not a fraction as pleasing to the ear).

In recent months, I’ve been fortunate to interact with activist teens, graduate engineering students, aspiring journalists and international development researchers. Intelligent, industrious and energetic, they’ve left me inspired by their intellectual gifts and commitment to making the world a better place.

I think many may also be extremely articulate, but that’s a harder call. Because the repetition of a single, misused word or phrase interrupts the flow of their ideas and renders every sentence a mottled pastiche of insights and valley girl talk.

Verbal crutches are common. Many of us unconsciously insert an occasional (or frequent) “um” or “ah” into our speech to buy thinking time. Others overuse “really” or tag “right?” onto the ends of sentences to engender agreement. And still others develop the habit of defaulting to “literally” or “in point of fact” for emphasis.

Nor is the dependency purely a symptom of youth. I’ve noticed similar verbal tics in corporate executives and university lecturers, policy experts and politicians.

These examples may suggest that such speech habits aren’t a deterrent to impact. Indeed, some have argued that speakers in intimidating positions who occasionally use filler words can come across as more relatable. And it’s true that not all listeners are as attentive to repetitive verbal crutches as someone who speaks often and trains others to do so, too.

But if a good portion of your airtime is devoted to meaningless words, they can’t help but detract from the substance of what you’re saying.

So, if you suspect yourself of relying on a verbal crutch or overusing one particular word until it becomes meaningless, here’s the three-phase cure:

1. Cultivate Awareness

Audio-record your voice when hanging out with friends or speaking with colleagues. Play the recording back and pay attention to repeated phrases or inserted tags. Replay it, marking a piece of paper every time you notice the crutch. Then listen a third time and try not to notice it.

Start to pay attention to the speech habits of others you interact with every day, especially your close friends, family members or colleagues. Are you reinfecting or reinforcing each other?

2. Clarify your Motivation

Think about the significant time and financial investments you’ve made in your own advancement: college diplomas, university degrees, professional accreditation, years of hard work, overtime, missed weekends or vacations …

Reflect on what other ambitions you may harbour: Promotion within your organization, a career change to another industry or leadership status of any kind.

3. Recruit Accountability Buddies

Deputize one or two people with whom you spend a lot of time to start counting how often you utter the crutch and commit to putting a loonie in a jar for every offence. Allow your accountability buddies to determine how the money gets spent.

Respond to your growing awareness by replacing your verbal crutches with pauses. This may feel awkward at first, but pause-inflected speech allows you to think, and others to absorb or reflect on, what you’re saying.

Create a calendar item that reminds you to re-record yourself every few weeks to note your improvement or backsliding.

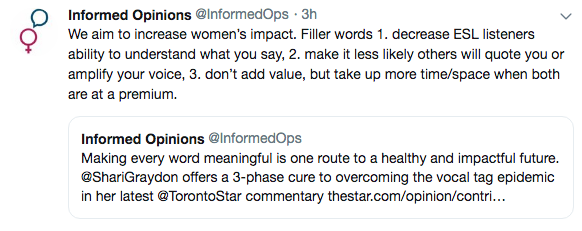

If you’re gifted with both the ability to speak and people willing to listen, making every word meaningful is one route to a healthy — and impactful — future.

Since the piece was published just a couple of days ago, I’ve had a number of interactions with readers. One respondent asked if Informed Opinions’ limited our amplification efforts to women who don’t use filler phrases. My colleague Samantha, who does all of the intake interviews, offers this context:

I’ve spoken to hundreds of experts and some have used filler during our conversations – academics, corporate, millennials, Gen X’ers. We’ve never said no to promoting a woman because she’s used “like” or “you know?” during an intake conversation. It’s been distracting at times, but I also know the qualifications which got us to the point of having a discussion with them to join the database. So, no, using filler hasn’t disqualified anyone from being promoted by Informed Opinions.

At the same time, our goal is to make it easier for journalists to find people who can provide context and analysis on important issues.

If you’re producing a radio segment or TV clip, and you have the choice to interview a person who intersperses her speech with filler phrases, or an equally intelligent one who doesn’t, you’re going to select the latter — for purely pragmatic reasons: she will be able to deliver — as Mark Twain once recommended — maximum sense with minimum sound.

I confess to being a bit baffled by the degree of resistance to pursuing communication that is both clear and concise.

When I’m told by an editor that she has space for only 600 words, I edit my writing as tightly as I can to share as much insight as possible, given the constraints. Similarly, whether I’m given 10 minutes or an hour to speak to an audience, I’m very deliberate about what stories I tell, what research I share, what words I use. I try not to waste people’s time with filler — or jargon, or acronyms — of any kind.

Realizing many people feel strongly about this issue, we’re seeking to expand the conversation for those not on Twitter and invite additional comments here.