Critical feedback is one key to success

by Shari GraydonAlbert Einstein – great lectures and, IMHO, great hair! photo by Oren Jack Turner https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=254353

“Great lectures, bad hair.”

Clearly, I’m no Einstein, but in the fight for my most memorable student evaluation as a university communications instructor, that comment from 1992 runs neck and neck with this one from 1998:

“Puncuashun, and speling, to strick.”

Translated, this means “Punctuation and spelling too strict.” (Which, I’m pretty sure, totally redeems me.)

As for the first critique, given the audience for the evaluations (people in a position to hire me again the following year), I decided better “bad hair” than “bad lectures”.

Having spent the better part of my professional life writing, I am perpetually on the receiving end of critical feedback. Speechwriting clients, book and newspaper editors, my significant other have all offered constructive advice on my first drafts. My writing is significantly better for the feedback, and my own editing skills have also improved leaps and bounds over the past three decades.

These days I spend more time at the front of a room than writing at my desk. But appreciating the Japanese concept of kaizen, or continuous improvement, I actively seek feedback there, too. Because it’s fundamental to effectiveness.

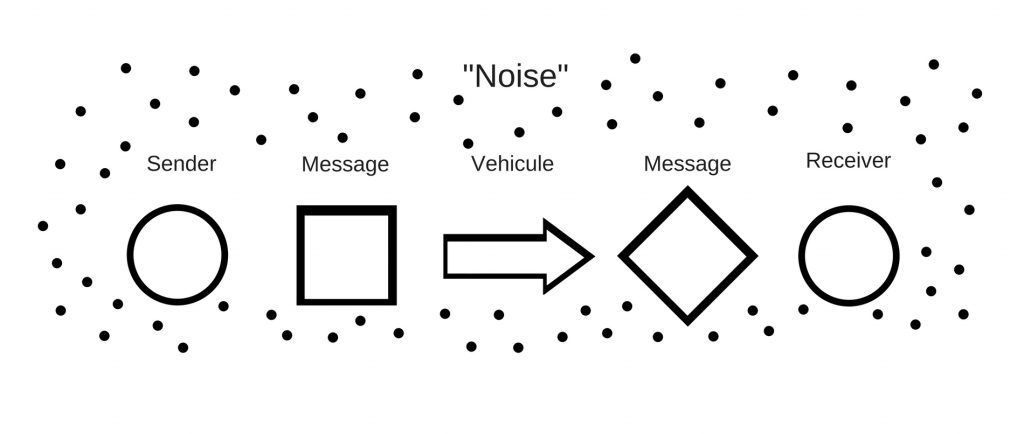

Consider the flow chart below.

I use this in every strategic communications workshop I deliver. Although most people have never seen a version of this chart, we all engage in the component activities reflected in it multiple times every day, usually without thinking about them. But given how central effective communication is to success – both personal and professional – it’s useful to make the process conscious.

Notice, for example, that the symbol for the message sent looks different from the symbol for the message received. Anyone who’s ever played the childhood game that we used to quaintly call “telephone” appreciates how easily that happens. (And being in relationships – with friends, family members or work colleagues – delivers the same lesson, every day and sometimes painfully.)

“Noise” – be it physical, psychological, emotional or circumstantial – plays major interference. As does the selection of the communications vehicle itself. Ever sent someone important information by email when the contents and context really warranted a face-to-face meeting? Something you only figured out when the email failed to elicit the desired response?

So when you’re undertaking high-stakes communication, it’s especially helpful to consider each of the flow chart’s pieces.

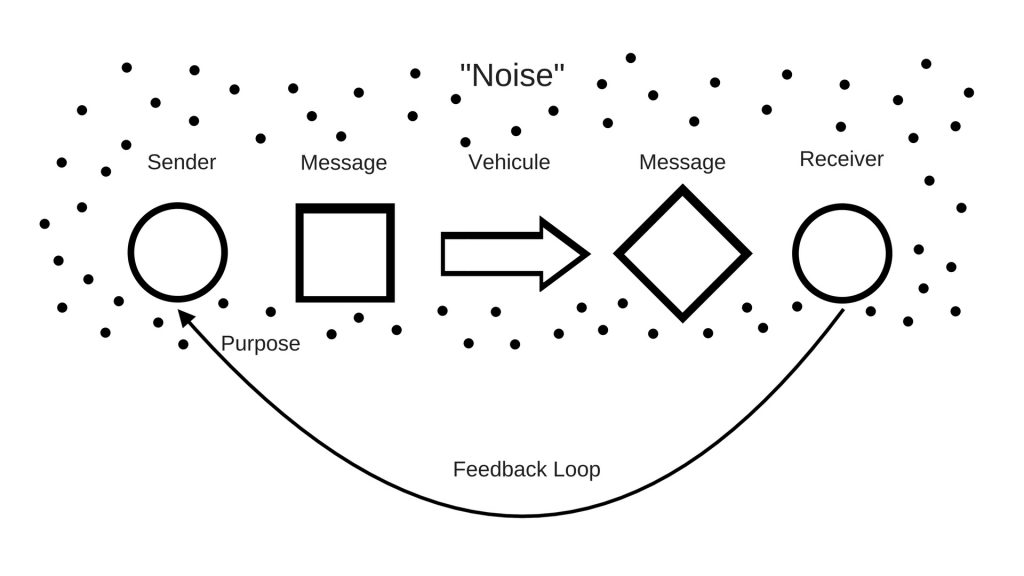

And yet, the version of the flow chart above is missing what is arguably the most important element: the feedback loop. Because without feedback, you have NO IDEA whether or not your communication was effective. And it’s something that should ideally be built into the process BEFORE the actual communication takes place.

Sometimes, the nature of the communication itself makes this easy. If you run for office, your goal is clear, and the outcome of the election provides the feedback loop: you either get elected or you don’t.

But often the feedback loop either isn’t built-in, or it doesn’t happen soon enough, and by the time we have the capacity to measure our success, it’s too late.

So if you do want to get better at what you’re doing, the first step is to attach a desired and measurable outcome to every piece of communication that’s important to you. This significantly enhances your ability to improve.

Take our aspiring politician. Does she invest in the latest technology and make sure every one in her prospective riding gets robo-called once a week? Or does she knock on doors and talk to people? The latter strategy may be much more time-consuming, but it offers an automatic and immediate feedback loop. It tells her what citizens care about and how they feel about her party, or whether they’re even aware there’s an election happening. The robo-calls do none of that; they don’t give candidates ammo to help them refine their messages or focus on the issues that actually matter to voters.

A feedback loop gives you invaluable information about what you need to work on if you want to increase your impact.

That’s why I barricade the door of my seminar rooms, refusing to let participants exit until they’ve completed a one-page evaluation. I print these on coloured paper to ensure I don’t overlook them in the last 10 minutes of the session. I read every one, and — for accountability purposes — I share them with the partners who host the workshops.

When I first started teaching women how to translate their knowledge into lively, accessible, relevant short-form media commentary, the seminars lasted a whole day. But initial feedback told me many experts who wanted to attend had difficulty finding the time. So I reduced the number of participants and made the sessions half a day instead. To accommodate the shorter time frame, I also adapted my feedback instrument to list all of the workshop components so participants could indicate which pieces they found most relevant.

Over the course of seven years, this feedback has helped me to refine and adapt what I do in ways that increase engagement and enhance impact. The workshops are more valuable for those who attend, and – knowing that – much more satisfying for me to deliver.

It’s true that – not wanting to distract my audiences – I still worry about bad hair days. (And to be fair, my 1992 critic is not entirely responsible for that obsession.)

But I remain very strict when it comes to punctuation and spelling. Because notwithstanding the value of feedback, the criticism you take to heart should reflect a genuinely informed opinion!