How journalists and universities can make it easier for experts to say “yes” to media interviews

by Shari Graydon

Journalists interviewing a female source (Shutterstock)

Nancy Worth is a rock star in our world.

After participating in one of our Writing Compelling Commentary workshops a little over a year ago, the University of Waterloo professor asked us if we’d be interested in collaborating on some research about our work. Then she developed the proposal, successfully applied to the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council for financial support, and oversaw the bulk of the work.

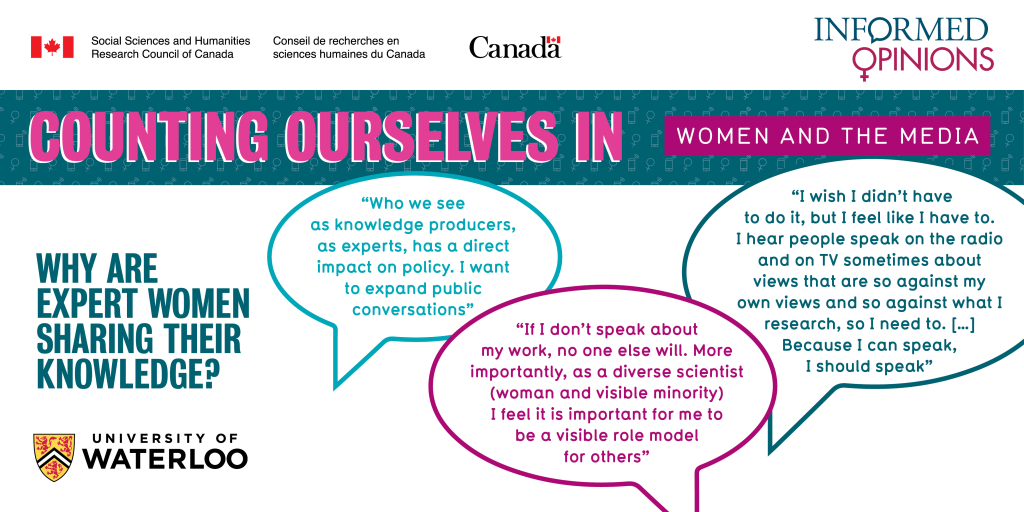

We’ve written before about the reasons women experts engage less often with media than their male colleagues. But Nancy’s initiative focused on what motivated the women in our growing experts database to “count themselves in.” Through a survey of 193 experts, and in-depth interviews with 34, we gained a deeper understanding of their reasons, experiences and the remaining barriers to women’s participation in media.

The resulting report, Counting Ourselves In: Understanding why women decide to engage with media, is now available online. It offers a concise and accessible overview of what we learned. In this post, we’re building on and extrapolating from some of the explicit insights about how journalists and universities can better facilitate women experts’ media engagement.

The women who’ve chosen to be listed in our database do so for a variety of reasons, but included among these is that they take seriously Albert Einstein’s dictum: “Those who have the privilege to know have the duty to act.” Many see media engagement as a form of public service.

But they’re usually very busy, juggling many competing demands. And for academics in particular, unless a media opportunity is focused explicitly on their research, the rewards of being quoted in a news story or featured on a talk show program are not always clear.

WHAT JOURNALISTS CAN DO TO HELP

- BE CLEAR ABOUT WHAT YOU NEED

“When journalists tell me in the email who they are, what they’re doing and why they’re interested in this story, that’s really helpful for me to figure out if this is something I know enough about and also is this a person I can trust.”

Many journalists are resistant to sharing their questions in advance of an interview. We get why this might be desirable when interviewing a politician or CEO with an inclination to give canned and unilluminating, versus colourful and authentic, answers.

But if you’re looking for hard data or insight related to a technical or scientific issue, emailing your questions to the source first is likely to result in much better, clearer and more helpful responses. They can review the relevant research, make note of the specific numbers, or come up with an analogy that will help your audience understand the topic more easily.

“I don’t need to know all the specific questions but are we going to talk about my research programme, about women in science, about soft skills… Sometimes journalists will also let me know who else they’re talking to. Knowing what others cover allows me to focus on another area that maybe is not going to be the super obvious piece.”

2. REDUCE THE AMOUNT OF TIME NEEDED TO PARTICIPATE

If you’re like most Canadians, you bank and/or shop online and so appreciate how much time doing so saves you. Although we regularly encourage the experts we train and support to go into the studio for an interview if they can (better sound and video quality, chance to build rapport with the host), the extra time required to do so is often prohibitive. This is especially true for those living outside of major centres.

Yes, YouTube is rife with bad Skype interviews (the intruding child! the barking dog! the ghoulish up-shot!), but these are all avoidable. The built-in cameras on laptops have improved significantly and most people, if reminded, can find a corner of their home that offers a backdrop relatively free of clutter, and lighting that will successfully illuminate their face, rather than leaving them in silhouette.

3. AVOID FRAMING THE ISSUE IN PRO AND CON TERMS

Debate style programs that require participants to be all-in on one side of a complex issue are often unappealing to thoughtful experts – especially women. Deep knowledge of a subject and the research underlying it usually means appreciating that studies sometimes contradict one another and explaining evidence accurately can require equivocation.

If, when soliciting the participation of a new source, you frame the issue in polarizing terms, and give the expert the impression that you’re looking for them to come down hard on one side or the other, don’t be surprised if you get turned down from those who know the most. They understand that stark pro or con framing can do a disservice to issues and audiences alike.

4. CHECK QUOTES ON COMPLEX OR TECHNICAL ISSUES TO ENSURE ACCURACY

What might seem like a minor error of slight rewording on your part can often provoke grave alarm from a source whose scientific reputation depends on her attentiveness to accuracy and nuance.

If you’re translating complicated or technical information about a subject you don’t know well, it’s worth double-checking your quotes. We’ve heard many scholars swear off doing media altogether after being seriously misrepresented by a journalist who – either due to carelessness or the desire to make material more accessible to a broader audience – inadvertently changed the meaning of the information shared in a way seen as egregious by the source.

WHAT UNIVERSITIES CAN DO

1. RECOGNIZE MEDIA ENGAGEMENT AS COMMUNITY SERVICE

“Really, in our line of work, you don’t get much credit. The time you spend on media work means less time doing your research, and it’s hard enough for women to try to climb up through the ranks in the university.”

The time scholars spend in administrative jobs and serving on adjudication committees is often recognized as service to the university. Media engagement helps policy makers and members of the public alike better understand complex issues. Acknowledging it in a systematic way would help.

2. PROMOTE A CULTURE THAT VALUES KNOWLEDGE MOBILIZATION

“I think universities need to offer more training, need to make people feel that this is valuable work, need to count or recognize it in some way.”

Scholars are trained in critical thinking, and the competitive nature of academic life reinforces the inclination to critique, rather than celebrate, others’ work – especially if that “work” might be perceived as “not serious”, or oversimplifying sophisticated theories or scientific concepts. At almost every university workshop we deliver, someone raises concerns about the likelihood of being criticized by colleagues for being a microphone hog.

This is a barrier to engagement that universities can help to overcome by actively celebrating the contribution that knowledge mobilization makes. And by reminding scholars that the research-informed insights they possess are most valuable when applied to addressing issues affecting people and the planet. Achieving that kind of impact becomes much more likely when the information is made accessible.

3. OFFER TEACHING RELIEF

As an encouraging sign, relative to the point above, some universities now offer an annual prize to scholars who have demonstrated significant knowledge mobilization through media. Given the hours of labour involved in preparing for, getting to and giving media interviews, offering some measure of teaching relief is likely to increase scholars’ willingness to aid in enhancing the university’s public profile.

4. MAKE IT PHYSICALLY EASY FOR SCHOLARS TO ENGAGE

Despite the fact that the University of Waterloo doesn’t teach journalism, its campus does boast a TV studio. This makes it much easier for faculty members and grad students to do professional quality TV interviews without having to battle traffic to and from Toronto on the congested 401.

Setting up a similar facility may not be possible for most campuses. But we’ve heard from a number of faculty members what a difference it would make to their own ability to engage with media if their institutions were able to designate a space on campus with professional equipment that would facilitate similar engagement.