So you have reservations about declaring yourself an expert…

by Shari Graydon

Photo by Andrea Piacquadio from Pexels

I often joke that I became president of MediaWatch (Informed Opinions’ predecessor) by going to the bathroom at the wrong time, and returning to discover I’d been elected president.

The line reliably nets me a laugh and a lot of “been there” nods from audiences of women (because a lot of us have been volunteered for jobs that need doing but are unlikely to net much recognition or reward).

As I recounted in an earlier post, I had no aspirations at my second board meeting to lead the organization. In fact, as an aspiring grad student who’d been rejected by my program of choice, I was certain my enthusiasm for the cause was eclipsed by my lack of knowledge and experience.

And yet I had spent months immersing myself in research and analysis of trends and implications of the media’s portrayal and representation of women. And I had translated my outrage over the discovery of these truths at the ripe old age of 29 into a handful of commentaries that had been published in national and local papers. These had led to additional broadcast interviews and a couple of speaking requests. The truth was I did have a more informed opinion about related issues than most people.

But I wouldn’t ever have used the word “expert” to define myself.

And since launching Informed Opinions 11 years ago, I have met hundreds of women — many with PhDs or decades of experience — who similarly question the relevance of the term in application to themselves. In fact, last year a doctor who was being encouraged to join the database cited imposter syndrome as her reason for declining. At the time, we had a graphic on our site of all the potential criteria that constituted sufficient expertise to be included in our list of reliable sources. But this MD had seen the list of credentials — education, professional experience, publications, awards, recognition, among others — as inclusive. She thought she had to tick all the boxes to be an expert.

This is in keeping with the research you’ve probably heard about finding that while male candidates are willing to put themselves up for a job or promotion if they have 60% of the qualifications, women are more likely to assume we need 100% to bother applying. Although both the stat and the notion that women suffer more from “imposter syndrome” than men have both been debunked (see an interesting analysis here of the former, and here of the latter), we still regularly meet women who hesitate to join our database, believing they’re not “expert enough” to be considered authoritative in their field.

So we removed the problematic graphic and revised our web page in an effort to make clearer to women how much they need to know in order to say “yes” to media interviews. Notwithstanding the above challenges to conventional wisdom, we continue to hear that women are more likely to default to thinking they must be “the best person” to respond to journalist queries. It’s why I named my last book “OMG! What if I really AM the best person?“

And so here’s what I encourage you to do when contacted by a reporter:

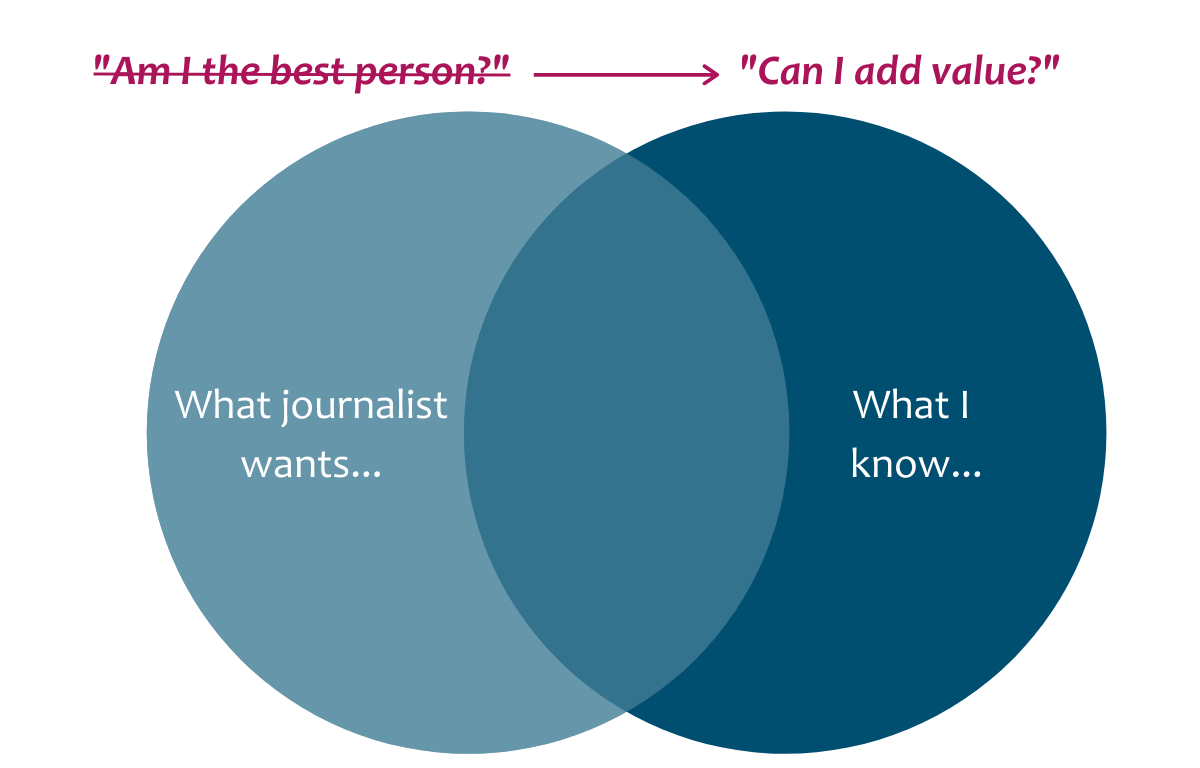

- Ask yourself not if you’re the “best person” (there’s no such thing), but if you can add value. And to determine that…

- Draw yourself a Venn diagram like the one below, looking for the intersection between what the reporter wants, and what you know. (Because there will be one, or you wouldn’t have been contacted in the first place.)

And then you make like my friend, Frances Bula, herself a seasoned reporter, and you say, “Here’s what I could talk about…”

In the meantime, check out the explanation below, which now has a permanent home on our site.

And please share this post with friends and colleagues whose expertise or informed opinions you think might benefit public conversations on any topic. When they’ve finished reading the post, encourage them to click on the “Apply to join” link.

What constitutes an “informed opinion”?

-

- relevant personal experience?

- relevant professional experience?

- relevant educational credentials?

- published thought leadership pieces on related issues?

-

- currently working or volunteering in this area?

- accredited by a relevant institution or professional organization?

- affiliated with an organization active on this issue?

- doing related research?

- recognized by others as being knowledgeable in this area?

Are you ready to say ‘yes’ to media interviews?

Being included in the Informed Opinions database means agreeing to respond to journalists’ requests. The women we feature recognize the value of having an amplified voice in terms of the potential it offers them to increase their profile, credibility and capacity to exert influence on the issues they know and feel strongly about. Many are pro-actively seeking to share their insights through blogs, opinion pieces and speaking engagements. You can apply here to join the database.

If you have informed opinions but are not sure you’re “media-ready”, we offer programming and resources to help you develop the skills necessary to effectively share your knowledge with a broader public.

Subject matter expertise isn’t always accompanied by training in how to craft thought pieces, frame analyses into accessible, short-form commentary, or package insights into sound bites.