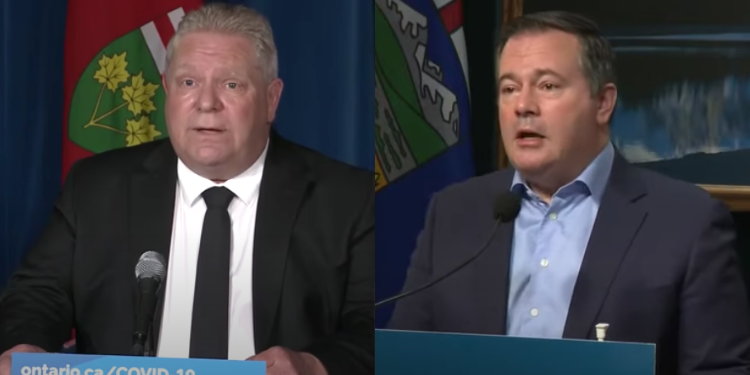

Four communication lessons from Doug Ford and Jason Kenney

by Shari Graydon Doug Ford’s mis-management of the COVID-19 crisis has put the Ontario premier in the crosshairs of parents, teachers, restaurant owners and frontline workers alike; it’s caused health care leaders to publicly weep in frustration.

Doug Ford’s mis-management of the COVID-19 crisis has put the Ontario premier in the crosshairs of parents, teachers, restaurant owners and frontline workers alike; it’s caused health care leaders to publicly weep in frustration.

Governing effectively in uncharted pandemic territory is like leading a country in wartime: the challenges are legion and unpredictable. Addressing them requires intelligence, compassion and decisiveness. And given the life and death consequences of leadership failure, strong communication skills are critical.

In this arena, sadly, the premier of Canada’s largest province frequently fails. Although his willingness to express emotion in daily press conferences at the start of the crisis initially softened Ford’s image, many of his recent pronouncements have sown confusion and mistrust. And every time he steps up to a microphone, he reinforces practices that we should all strive to avoid.

Here are three “what-not-to-do” communication lessons from Mr. Ford and one from Mr. Kenney:

- Cede the floor to others who are better equipped to convey complex information

At Informed Opinions, we regularly encourage under-represented experts who decline interview requests by confessing “I’m not the best person” to keep the door open by changing their response to “Here’s what I could talk about.”

But offering to share what you are expert in is different than putting yourself front and centre even when others are much better suited to communicating the issues at hand — especially when they have life-threatening implications.

Early on, BC premier John Horgan ceded the floor to his province’s Chief Public Health Officer, Dr. Bonnie Henry, who has earned national appreciation for her communications effectiveness. (Sadly, Ontario’s own CPHO is, like his premier, not a stellar communicator. But Ontario is home to thousands of medical and research professionals and Christine Elliot in her role as Minister of Health might also have been a much more effective spokesperson.)

- If you must read a script, do so with energy and inflection

I had never heard Doug Ford deliver a speech until the night he was elected premier in 2018. I was shocked at the woodenness of his delivery, the cadence of every sentence following the same repetitive vocal pattern, inviting his audience to tune out.

Three years later, even though public speaking is central to his job and he’s had daily practice, he remains incapable of reading text aloud with authenticity and presence. As a result of his unvarying vocal inflection, it’s much more difficult for audiences to remain attentive to or feel the emotional context for the message. Repetitive patterned speech also makes it harder for listeners to trust that the messenger has the insight and executive decision-making skills necessary to the critical position he holds.

- Prioritize clarity over politics

Ford has frequently used the terms “lockdown”, “shutdown” and “emergency break”, even when the measures he was announcing did not dictate that people should stay home. I suspect this waffling is a function of knowing he needs to stop the spread of the virus, but fearing he’ll raise the ire of voters who question the restrictions.

Playing politics with language in a pandemic puts lives at risk and exacerbates citizen resistance, as Ford’s Alberta counterpart, Jason Kenney, has also discovered. As a result, both men have delivered mixed messages that have confused rather than clarified what measures are actually necessary to slow infections and save lives.

- What you say first shapes how we hear what you say next

For his part, Premier Kenney begins many of his press conferences with statements that completely undermine his subsequent pleas to Albertans to follow lockdown measures.

Last week, less than 30 seconds into his introduction of desperately needed new restrictions, he stressed his commitment to “resisting pressure to implement widespread and long term policies” because “governments must not impair peoples’ rights or their livelihoods…”

Such statements, rather than appeasing mask-defying Albertans angered by business restrictions, end up becoming the filter through which they hear everything he says next. By privileging their concerns, he is inadvertently feeding the resistance, reinforcing their certainty that their actions are justified.

“All great speakers were bad speakers first.”

So claimed American writer and lecturer, Ralph Waldo Emerson. My own 30 years of experience — speaking, attending conferences and lectures, and coaching others — suggest that although some people may be born with more assets than others — confidence, creativity, a sense of humour — everyone gets better with effort.

Consider Britain’s war-time prime minister, Winston Churchill, as just one notable example. He is remembered not only for his leadership in crisis, but for his exceptional oratorical abilities. But he wasn’t a born speaker. At the start of his career, he spoke in a monotone and had difficulty pronouncing the letter “s”. However, understanding that his ability to engage and inspire audiences was critical to his effectiveness, he worked at it.

Anyone who aspires to run for office or influence people in other public roles needs to do the same. Informed Opinions’ highly rated, interactive workshops have supported almost 4,000 experts in improving their communications impact.

You can join them in learning practical skills that will support you in speaking or writing more effectively. Sign up here to be notified of upcoming workshops.

Looking for customized training? We provide a range of tailored workshops to suit the needs of any organisation. A list of all our offerings can be found here.

Shari Graydon is the Catalyst of Informed Opinions, a non-profit working to amplify the voices of those who identify as women, Two-Spirit and gender-diverse and ensure they have as much influence in Canada’s public conversations as men’s.