How will we spend the $1 trillion coming our way?

by Shari Graydon Did you hear about the woman who left her small fortune to a potted plant because it was “the only thing that listened to her”?

Did you hear about the woman who left her small fortune to a potted plant because it was “the only thing that listened to her”?

As relatable as the sentiment might be, the truth is that women are a growing force when it comes to donating to charities generally, and to social justice causes in particular. And according to an analysis conducted by TD Wealth Advisory Services, that trend is likely to benefit from the vast sums of money Canadian women are expected to inherit from their partners and parents over the next decade.

Did we say “vast”? The predicted infusion is – wait for it – a trillion dollars.

Not all of that money will be given away, of course, but some of it will. And in a post-#MeToo era, when women’s voices on every issue have more opportunity to be heard than ever before, what causes are most likely to attract greater support from women themselves? And what changes might such support bring about – not just for women, but for society and the planet more broadly?

There’s no predicting (though our word cloud experiments might offer some clues). But almost a decade ago, Gloria Steinem was already ahead of the curve in anticipating the need to pay attention to this transfer of wealth. In 2010, the same year we launched Informed Opinions, the respected US activist wrote a letter to Canadian donors who care about women. In it she encouraged us to ask the following questions when deciding where to contribute:

-

Is the project creating change?

-

Does it include the true diversity of women and girls affected by the problem?

Longstanding feminist philanthropist, Shirley Greenberg

Interestingly, Shirley Greenberg, a longtime philanthropist in Ottawa who has supported women’s initiatives large and small for decades (including Informed Opinions), told me a few years ago that she had changed her own approach to donating. Although she’s been extremely generous to both hospital and university campaigns, she now privileges smaller, feminist organizations that don’t have the fundraising machines of big institutions, and are focused explicitly on equality issues.

It seems she’s not alone. The TD review of research on women and philanthropy cited a 2016 US Trust Study that found women to be much more likely than men to make giving decisions based on “the pressing issues of our time”.

In part, this is because more women believe “that non-profit organizations have the ability to solve societal and global problems.” (I share this belief – but the irony is that we have vastly fewer resources than the entities that are creating the problems!)

Activist and philanthropist, Roslyn Bern, head of the Leacross Foundation

TD’s report referenced another study done by Strategic Insight which found that “men equate wealth with achievement and prestige, while affluent women view wealth in terms of financial security and the ability to influence the well-being of both their families and of those less fortunate.” This jives with other research into the effectiveness of micro-loan programs for women in developing countries, and is also reflected in the philosophy of Roslyn Bern, head of the Leacross Foundation (who, I’m happy to say, also generously supports Informed Opinions).

Roslyn is so deliberate about looking for impact in the projects she funds that she regularly participates in site visits, pilot programs and exit interviews. And her active engagement reflects another research finding: women are more likely to respond to invitations to “support causes that have been important in their lives” than to appeals to “leave a legacy”.

In fact, this mirrors what we hear at Informed Opinions when we ask women about their motivation to be heard. So many of them tell us that their willingness to take the risks involved in speaking up is less about fulfilling career goals and more about making positive change in their communities, or being a good role model for others.

We’re proud to be able to answer “yes” to both of Steinem’s questions. We receive feedback on an almost daily basis from women who’ve participated in our workshops, or been featured in our database, about the difference their subsequent engagement or amplified voice has made as a result.

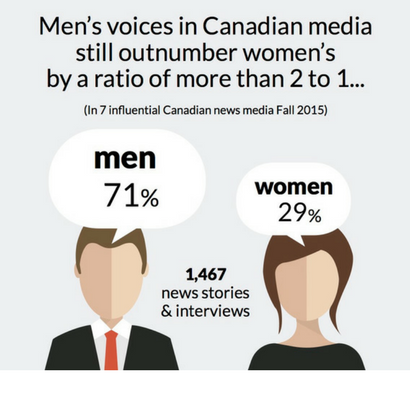

And on an aggregate level, when we began this work in 2010, male voices in Canada’s most influential news media outnumbered women’s voices by a ratio of four or 5 to 1 — as they had for the previous 20 years. Within 5 years, our work had helped change the ratio to 3 to 1. And we have a clear plan to finish the job. (You can donate here to help make it happen.)

As for reflecting the true diversity of women and girls affected? We’re tracking that, too, but a quick scroll through our online expert database will make clear how well we’re doing on that front.

In her letter, Steinem also reminded potential donors that:

“Thousands of woman hours could be saved by reducing grant-writing.”

Our small team – like every other women’s organization I know – has, indeed, invested thousands of hours writing grant applications. And we’ve sometimes succeeded in accessing government funds to support aspects of our work.

But we’ve been even more fortunate to benefit from the no-strings-attached monies given by individual donors and supporters like Shirley, Roslyn, former Senator Nancy Ruth, and many of you. As Steinem points out in her letter, these have allowed us to minimize the time we devote to explaining and justifying our work, and to maximize the time we actually spend doing.

In our case, that doing has both individual and systemic impacts. By supporting women to speak up, and making them easier for journalists to find, we are not only increasing their individual opportunities, but also ensuring that Canadians more broadly benefit from their uniquely informed opinions.

In our case, that doing has both individual and systemic impacts. By supporting women to speak up, and making them easier for journalists to find, we are not only increasing their individual opportunities, but also ensuring that Canadians more broadly benefit from their uniquely informed opinions.

In my talks and book, OMG – What if I really AM the best person?, I point out an obvious but frequently overlooked fact: that most women spend decades of our lives either trying to avoid becoming pregnant, trying to become pregnant, or dealing with the consequences of having been pregnant. Which not only last forever, but change so much — our bodies and brains, our perceptions and priorities, the way we look at the world and the way we’re seen and treated by others.

So if our voices are absent from the public conversations that inform policies and programs, entire swaths of human experience are not being taken into consideration. And you can’t make policy that will effectively address the needs and concerns of the entire human family if you’re mostly hearing from just half of it.