Unconscious Bias and the Right to Bare Arms

by Shari GraydonRecently I shared the link to a blog post written by a writer whose insights I have often found relevant, useful and supported by research. My 200-character comment suggested that speakers who wanted to be taken seriously should cover up their arms. A minor storm ensued. I regret my failure to review the original study being cited, and provide more nuanced context. Here, belatedly, is a better summary of what I understand from related research and personal experience.

In the immortal words of Martin Luther King, we all have the right to be judged by the content of our character, not the colour of our skin, or, I’d like to add, the amount of it that’s on display.

Among the many obstacles between this ideal and the reality is unconscious bias. In pursuit of survival, our limbic brains have, over centuries, developed the capacity to register and integrate bits of information so quickly that the conclusions we draw and the decisions we make occur without us being consciously aware of the process.

This remarkable capacity permits us to leap out of the way of speeding vehicles and answer tough questions when a microphone is thrust in our faces. But it also frequently steers us wrong, causing us to draw erroneous conclusions based on unreliable cues culled from among the millions of bits of visual, aural and sensory data that we’re exposed to every second.

As a result, without realizing it, even the best-intentioned and aware among us, often make assumptions based on superficial appearances. Our fast brains rely on stereotypes — reinforced by countless impressions delivered by media images and messages of all kinds — to equate gray hair and wrinkles with technological incompetence, and a direct, open gaze with honesty.

The impacts of unconscious bias — on women’s perceived credibility in sexual assault trials and on the opportunities we’re given in professional contexts — are punishing, pervasive and well-documented. Thankfully, the #MeToo movement is helping to address the former, and governments and universities are actively seeking to reverse the latter. The end goal is to overcome the barriers currently preventing women in all our diversity — including those affected by intersectional dimensions — from being accepted and believed, hired and promoted on a level playing field with our male colleagues.

On being “read” visually

I used to write and perform short commentaries on CBC TV about various aspects of media influence. My full-time job, however, was teaching business communication to college students. Occasionally one of them would see me on TV. This did wonders for my stature in the classroom, but it also taught me something important: my students rarely remembered what I had been talking about, but they almost always recalled what I had worn.

We are visual creatures. That’s why storytelling relies so heavily on concrete images – TV, film and picture books obviously, but also novels which succeed in evoking visually-rich fictional realities.

Prior to being hired to deliver TV commentaries, I used to contribute 3-minute radio pieces to CBC. Over the course of several years, I developed a lovely relationship over the phone and by email with an intelligent and collegial producer in Vancouver. When we eventually met in person for the first time and she discovered that I’m small and blonde, she exclaimed in surprise, “Oh! I thought you were tall with dark hair!”

She, in fact, is tall and has dark hair. Because we got along so well, I think she inadvertently projected her own physical qualities onto my disembodied voice. I was not insulted by this demonstration of unconscious bias.

My work frequently requires me to stand at the front of a room. My goal in every case is to speak to the people assembled in ways that will permit them to attend to, understand and benefit from what I’m saying. Recognizing how easy it is for all of us to be hijacked by distractions, I am very deliberate about seeking to minimize visual interference.

Another way to put this is I dress to be heard.

Images of women are in plentiful supply in the media. Musicians and models, reality TV stars and athletes often dress in ways that emphasize their physicality. Sometimes that’s practical: some impressive feats are more easily performed when unencumbered by restrictive clothing. But often the emphasis on physicality is deliberately sexual, in aid of selling music or beauty products, or a “brand”. We are meant to notice the skin on display, and primed to associate its visibility with desire.

Let me be clear about this: I fully support every woman in wearing whatever she likes and feels comfortable in. There was absolutely zero body-shaming content in my tweet, or the article or research that inspired it.

At the same time, out of strategic self-interest, I choose my wardrobe to diminish the likelihood that my audiences will focus on something other than my ideas.

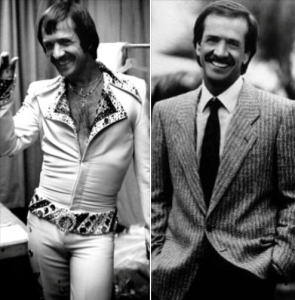

Finally, although the ways in which we judge women are more numerous and unfair, men are also vulnerable to this kind of unconscious bias, regularly seeking to mitigate it in order to be seen and heard. When Sonny Bono was the other half of Cher, he favoured very tight-fitting pants and often unzipped his body suit to reveal his chest hair. When he ran – successfully – for political office, he wore a dress shirt, tie and sports jacket.

Like many, I yearn to live in a world free of the unconscious bias that causes us to make unfair assumptions about others. I seek to become more aware of my own. But I also know that pretending bias doesn’t exist, or condemning people who acknowledge its impact, doesn’t help anyone. If we can’t talk about it – with respect – we’re never going to change it.